This article is part of a series that stems from my notes during the migration of an Exchange organization from version 2010 to 2016. This is not a complete procedure, but a description of the main points and areas. The examples relate to a specific given design, but can generally be generalized. Similarly, although it is a description of the transition to a new version, the information is also suitable for a new installation or management.

Official documentation for Exchange Server 2016. An article (also referenced in the official documentation) on this topic was published on TechNet: Namespace Planning in Exchange 2016. Additionally, the following articles may be helpful: Exchange Server 2016 Migration - Reviewing Client Access Namespaces, Client Connectivity in an Exchange 2016 Coexistence Environment with Exchange 2013, Site resilience.

Client Access Namespaces

First, a clarification. In this article, and elsewhere, I use the terms address and domain name (or DNS name or just name) interchangeably (perhaps not entirely accurately), for example www.company.com. Something else is an IP address, an example being 80.0.0.1.

The term Namespace, in Czech jmenný prostor (in some cases also adresní prostor), is used somewhat differently in the context of Exchange Server 2016 than I am used to. In practice, we most often encounter Domain Namespace, that is, the domain name space. In the context of DNS, where we have, for example, the Namespace company.com and within this domain we create individual records (names - addresses). This also applies to AD DS, which is based on DNS, we have, for example, the AD DS domain company.local. Another example is MAC addresses, where manufacturers have been assigned a certain Namespace (example 00:15:5d belongs to Microsoft) and within it they can create addresses.

In the description of the Exchange server, it is stated everywhere that various client connection services use some Namespace. For example, the Autodiscover Namespace or the Exchange ActiveSync Namespace. These are DNS names to which the client connects using Outlook, a mobile device or a web browser. So the usual addresses like mail.company.com and autodiscover.company.com. So the whole planning of namespaces means assigning one or more domain names to services (different services can share the same name).

Microsoft states that for Exchange 2010, a number of separate addresses were required (the article referenced above mentions 7, but that list seems strange to me) and if we used multiple sites (Site), separate addresses had to be used for each. In contrast, Exchange 2016 greatly simplifies the situation, and we can use a common address for most services (it is stated that 2 are sufficient, and I agree, but different than the ones mentioned in the article).

Internal and External Names and Split-Brain DNS

When planning addresses, it depends on whether we have the same domain externally (on the Internet) and internally (AD DS), for example company.com. Then we can have the same names for connection within the company and from the Internet. Or internally we use some non-public domain (or a different one than on the Internet), such as company.local. In the past, it was recommended to have a non-public internal domain, but today we are more inclined to use the public one.

Split-Brain DNS

Furthermore, we can use Split-Brain DNS (also referred to as Split DNS or Split-Horizon DNS). This means that there are two versions of the same DNS zone (domain) and they can provide different information. Typically, one zone version for internal users (when connecting from internal addresses) and the other within the Internet (when connecting from public addresses). Theoretically, it can be a single DNS server that returns responses based on the connection. But it is more likely that there are different DNS servers, the internal one is only available within the company, the external one is usually managed by our public domain.

Internally Public Domain

If we have the same internal AD DS domain as the public domain, then we are most likely always using Split DNS. The internal zone can return internal IP addresses for the same names that are translated to public IP addresses on the external DNS server. The external DNS will not have a number of internal domain names and records, which may relate to the AD DS domain.

It is important that if we create a zone (such as company.com) on the (internal) DNS server, this server responds only with its own records for the entire specified Namespace (domain, i.e. *.company.com). If some DNS name does not exist internally, it will not be redirected to the external DNS server where it might be. So we need to create all the records that are on the external DNS server (if they are to be accessible internally).

Internally Non-Public Domain

In the case where we have an internal AD DS domain different from the external one, the internal DNS usually contains a zone only for the internal name, and the translation of the public domain is performed by the public DNS (the request is forwarded). If we need some names to return a different IP address internally than externally, we can use Split-Brain DNS. Maintaining all domain names twice may be unnecessarily demanding. You can use (under certain conditions) a small trick and create only selected records Different IP address from DNS internally and externally.

Service Addresses

We have described the above to explain that for Exchange services for client connections we can configure an internal address (internal host name / URL) and an external address (external host name / URL).

Used Domain Names and Services

Most client connections to the Exchange server are now made using the HTTPS protocol (even if it contains encapsulated MAPI). This means simplification of traversals, connections, protocol standardization, but also the need to properly manage certificates. Now Outlook should handle network changes (e.g. LAN to WiFi) and startup from hibernation. Other client protocols are POP3 and IMAP4, which we may not need to use. The SMTP protocol is more server-side. We need to plan domain names for SAN (Subject Alternative Name) certificate planning as well.

Nowadays, it is recommended not to use server names directly in service settings, but DNS aliases or separate Host records, which I will call virtual names. Thanks to this, when changing servers (migrating), there is no need to change client settings (and possibly notify them of new URLs), but only to assign a different server to the virtual name. Load Balancing can also be used.

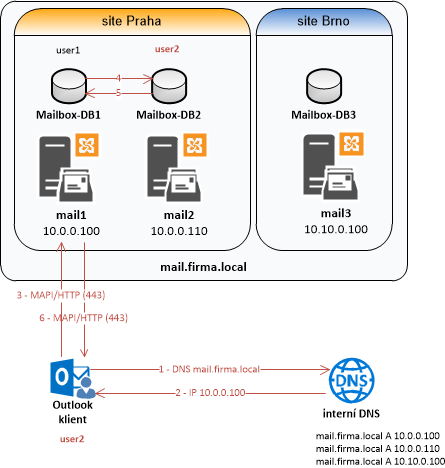

Virtual FQDN (Fully-Qualified Domain Name) name can have addresses of all Exchange servers assigned. Users only know one address and clients connect (balanced) to all servers. In Exchange 2010, the CAS Array worked this way, which no longer exists in Exchange 2016, but we can natively use (thanks to the HTTP protocol) DNS Load Balancing (Round-robin DNS). In principle, it still seems the same to me, we just don't configure the CAS Array.

Example addresses:

- Exchange Server 1: FQDN

mail1.company.local, IP10.0.0.100 - Exchange Server 2: FQDN

mail2.company.local, IP10.0.0.110 - Exchange virtual name: FQDN

mail.company.local, IP10.0.0.100, 10.0.0.110

An important feature of Exchange Server 2016 is that the client can connect to any server and the communication is proxied to the server where the mailbox is located.

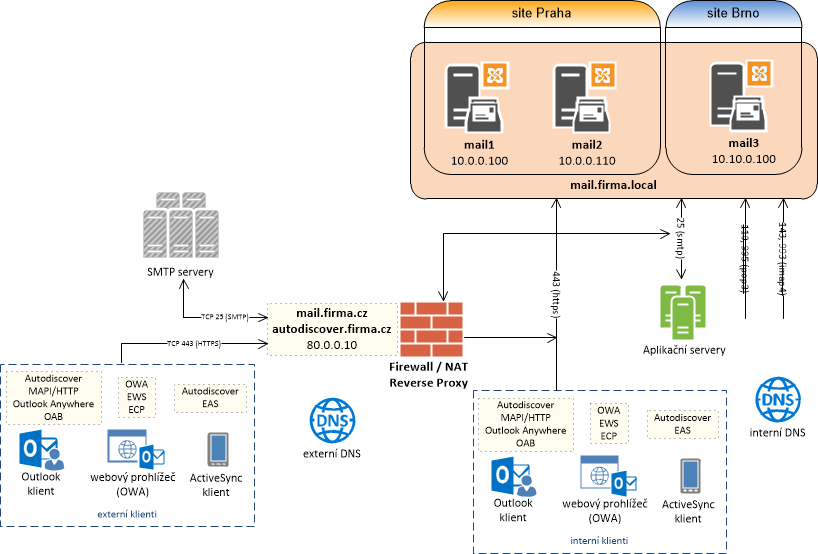

Connection from the Internet (external)

In Exchange 2010, I used different public domain names and public IP addresses. One of the reasons was also the different authentication methods (for different services) that took place on the firewall.

In Exchange 2016, the general recommendation is to use only one public IP address (unless we are solving redundancy at this level) and to it one A DNS record and one alias (CNAME). An example is the domain name mail.company.com with the public IP address 80.0.0.10 and the alias autodiscover.company.com for the same name (we can even do without it and use the SRV record). We will use this name for all client services and for the SMTP protocol. On the external firewall, we publish the SMTP protocol to the AntiSPAM gateway in the DMZ and HTTPS through the Reverse Proxy to the Exchange server.

Internal Connection (internal)

One server

Internally, the situation is more complex, depending on how many servers we have and how many sites. As we described above, even in the case of a single Exchange server, it is recommended to change the default setting of client services, where the default domain name of the server is set, to virtual name.

Multiple servers

If we have multiple servers, the same applies, on all servers we set a common virtual name for all services (DNS A record with IP addresses of all Exchange servers). Clients will be balanced on servers and communication will be proxied to the mailbox server with the mailbox.

Multiple sites

The most complex situation is when we have multiple sites (Site) and Exchange servers in them. Microsoft does not describe this entirely unambiguously, but I understood that the best is also to use a single common virtual name and assign addresses of all servers in all sites to it. Exchange 2016 handles Site resilience, so it's not a problem.

According to my tests, it works like this: for example, a client from a branch office receives the server address in the headquarters, connects to it, and the traffic is internally forwarded to the server at the branch office (where they have their mailbox). The client does get access to the mail, but the session does not go directly to the server they have at the branch office, but through the headquarters. This is unnecessary load and slowdown. The advantage is that if we have a DAG and one of the servers fails, the client connections still work (the DB copy is activated on another server and the clients are routed to it, using DNS to connect to the running server). It's a pity that there is no redirection (to establish a direct session) to the server where the client has their mailbox, instead of forwarding the communication.

If we don't want it this way, we have to use a special virtual name on the server at the branch office, where only the servers at that branch office will be. Autodiscover will ensure that the client always gets the address in their local area.

Planning addresses for services

We should have documented the current state with Exchange 2010 and now prepare a plan for the new state with Exchange 2016. Create tables (and possibly also diagrams) with a list of servers (names and IP addresses) and planned services (internal and external FQDN) and for their internal and external IP addresses.

Note: If we are currently using DAG and CAS Array, we have a DAG VIP and domain names for both DAG and CAS Array. We can now configure the DAG without them, and the CAS Array is not used at all.

Example list of mail servers

- FQDN

mail1.firma.local, IP10.0.0.100, SitePraha - FQDN

mail2.firma.local, IP10.0.0.110, SitePraha - FQDN

mail3.firma.local, IP10.10.0.100, SiteBrno

Example list of mail services

Note: Instead of a list, a table would be more clear. It's enough to write the FQDN (like mail.firma.cz), and for interest, we can also include the full URLs.

- primary SMTP domain

- firma.cz

- MAPI over HTTP

- Internal: mail.firma.local

- Internal URL:

https://mail.firma.local/mapi - External: mail.firma.cz

- External URL:

https://mail.firma.cz/mapi

- Outlook Anywhere

- Internal: mail.firma.local

- Internal URL:

https://mail.firma.local/rpc - External: mail.firma.cz

- External URL:

https://mail.firma.cz/rpc

- Outlook on the web (OWA)

- Internal: mail.firma.local

- Internal URL:

https://mail.firma.local/owa - External: mail.firma.cz

- External URL:

https://mail.firma.cz/owa

- Exchange Web Services (EWS)

- Internal: mail.firma.local

- Internal URL:

https://mail.firma.local/EWS/Exchange.asmx - External: mail.firma.cz

- External URL:

https://mail.firma.cz/EWS/Exchange.asmx

- Exchange Control Panel (ECP)

- Internal: mail.firma.local

- Internal URL:

https://mail.firma.local/ecp - External: mail.firma.cz

- External URL:

https://mail.firma.cz/ecp

- Offline Address Book (OAB)

- Internal: mail.firma.local

- Internal URL:

https://mail.firma.local/OAB - External: mail.firma.cz

- External URL:

https://mail.firma.cz/OAB

- Exchange ActiveSync (EAS)

- Internal: mail.firma.local

- Internal URL:

https://mail.firma.local/Microsoft-Server-ActiveSync - External: mail.firma.cz

- External URL:

https://mail.firma.cz/Microsoft-Server-ActiveSync

- Autodiscover

- AutoDiscoverServiceInternalUri: https://mail.firma.local/Autodiscover/Autodiscover.xml

- External: autodiscover.firma.cz

- External URL:

https://autodiscover.firma.cz/Autodiscover/Autodiscover.xml

Note: For connecting from Outlook internally, the MAPI/RPC protocol was previously used, and for connecting from the internet, Outlook Anywhere (MAPI/RPC over HTTP - that's MAPI inside RPC inside HTTP). Now the main protocol is MAPI over HTTP (MAPI encapsulated in HTTP), if the client doesn't support it, it will use Outlook Anywhere.

Domain names and IP addresses

- FQDN

mail.firma.local, IP10.0.0.100, 10.0.0.110, 10.10.0.100 - FQDN

mail.firma.cz, IP80.0.0.10 - FQDN

autodiscover.firma.cz, aliasmail.firma.cz- IP80.0.0.10

Note: Even if we have a non-public internal domain, we can use Split-Brain DNS and use only the public domain name everywhere.

Determining the current configuration

When we want to list the current configuration, we can search for something in the GUI, better list the configuration of individual services using PowerShell or maybe use a prepared script that lists everything at once GetExchangeURLs.ps1. This way we can also check the configuration of all servers to see if we've forgotten to change an address somewhere.

If we use the POP and IMAP protocols, we can list the important details.

Get-PopSettings | FT *ConnectionSettings,X509* Get-ImapSettings | FT *ConnectionSettings,X509*

Ahoj, jak vypublikuju ten exchange? na routeru nastavím na veřejnou adresu např mail.firma.cz ? neob se to nastavuje ještě někde v exchange? díky :)

respond to [1]Amatér: V podstatě stačí takto (i když by to chtělo provoz zabezpečit a využít alespoň Reverse Proxy). Nastavení bude popsáno v dalším díle.